“Looking towards recovery, this analysis of labour market exposure gives some hints as to how local sectors might bounce back. The key is how much and how fast pent-up demand is fired up and how efficiently and quickly supply chains react. Also, any upturn will reflect relative dependence on external trade and whether firms are subject to adverse or positive effects from the UK transition deal.”

Emeritus Professor, Nigel Jump, shares the next in his series of blogs, looking at the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the local economy.

CURRENT SITUATION

Why has the UK stock market been weaker than most others through 2020/21? Simply, because expectations about relative returns are more subdued for companies reliant on a country that is creating a) barriers to trade, b) uncertainty of crisis management, and c) less foreign direct investment (FDI). A UK future of lower growth and unemployment, incomes and profits, and wealth and well-being than its competitors is being discounted by the securities markets.

To turn these relative restraints around, the UK will require high quality investment in skills, structures and innovation, encompassing more entrepreneurship and stimulating competitiveness. A stronger foundation for development is needed; one based on investment in higher productivity activities that create high value and promise better living standards. That last sentence could have been written at almost any time in the last twenty years. It is particularly pertinent, however, at this juncture of crisis for UK regional economic development.

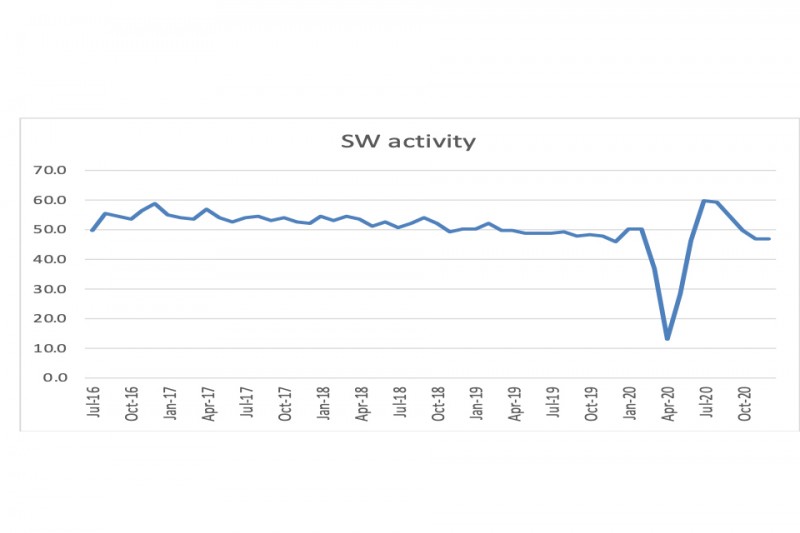

Meanwhile, as shown in the chart below, the latest SW activity index continues to trace out a lopsided ‘W’ shaped pattern. With output contracting over the last three months of 2020 (PMI readings below 50 – left hand axis) and, given lockdown 3, not expected to bounce back in Q1 2021, renewed recession seems inevitable. Perhaps, if wider vaccination and lower infection rates allow the business lockdown to be lifted and households to spend accumulated cash surpluses, the activity curve will turn positive (above 50) from the second quarter.

For now, though, that is a hope rather than a forecast. For months to come, it will be difficult to predict when the final upward leg of the ‘W’ will get underway and be secure. One concern is that the SW employment PMI is also negative: jobs are contracting. One hope, however, is that the measure of business expectations about future activity remains stubbornly positive. As the tide of the COVID-19 pandemic ebbs, there is a prospect of a strengthening rebound. The balance between job losses and savings release will be crucial in determining whether, and how much, economic growth is positive for 2021.

Over the last year of the COVID-19 pandemic, the local labour market has lost its normal ‘churn’. More sectors and businesses are ‘open’ during Lockdown 3 than during Lockdown 1, especially in construction and manufacturing, but not in retail, leisure and hospitality. A recent EMSI report suggests new job postings, an indicator of live vacancies, were down about 13% across SW England and workforce jobs were down about 3% through most of 2020. SW postings have yet to recover to pre-Lockdown 1 levels and are weak in three industries in which local Dorset businesses specialise: aerospace, accommodation and construction. Changes are more negative for SW postings and jobs than most other regions, but not as bad as the worst affected areas.

Other EMSI data that measures ‘furlough’ trends against location quotients, indicating relative sector reliance by geographical area, show SW accommodation and other visitor economy sectors badly exposed to Lockdown 3. SW manufacturing, construction and distribution are also moderately vulnerable, especially compared with the better local relationships in financial services, professional and information services, and some parts of transportation.

Across SW England, as one might expect, there are clear differences for the larger cities versus the rest, reflecting variations in industrial structure and business concentration. Within Dorset in particular, where claimant counts soared and postings withered in 2020, the sector concentration - e.g., financial services in Bournemouth, machining in Poole, electronics and systems in Christchurch, and health and care across the county - is an important guide to where current skills gaps exist and need to be addressed. In recovery, the demand for skilled trades and professional expertise and trainability will be strong and their supply paramount for a buoyant upturn.

CURRENT PROSPECTS

Looking towards recovery, this analysis of labour market exposure gives some hints as to how local sectors might bounce back. The key is how much and how fast pent-up demand is fired up and how efficiently and quickly supply chains react. Also, any upturn will reflect relative dependence on external trade and whether firms are subject to adverse or positive effects from the UK transition deal. Another important question is the relevance of new technological developments in AI/digital and environmental products and services amongst local firms.

These three main areas of local economic exposure – changes in a) pandemic policies; b) export trades; and c) new technologies – will dictate business growth prospects and employers’ demand for skills. As a sustainable recovery gets underway, regional skills planning and wider curriculum development for the 2020s need to reflect, and effect, an increase in competitiveness that stems from meeting these three growing influences.

Meanwhile, the forecasting consensus expects a global macro recovery to evolve in 2021 - and more so in 2022 and 2023.

- Optimism stems from the vaccine roll out, the release of a flood of excess savings - at least for higher wealth households, although there is some UK concern that this will disproportionately suck in imports - and the stimulative thrust of US President Biden’s policies - fiscal spending on the pandemic, infrastructure and the wider economy.

- Pessimism reflects concern about virus variants and virus ‘wars’, withdrawal of government emergency support for household demand and employment, and deglobalisation of trade. Shortages or price rises for key outputs and logistics are feared.

The global consensus is for at least 5% world growth this year, ranging from high plus numbers for China, the USA and some emerging markets and flatter numbers for EU, UK et al. UK growth for 2021 and 2022, assuming a sustainable end to the pandemic and lockdown, is forecast at 4.5-6.5% real growth per annum, with a return to pre-pandemic activity levels later in 2022/23.

A lot depends on household behaviour after recent shocks, particularly with respect to precautionary savings and the marginal propensity to consume and especially for domestic goods and services. The degree of permanent scarring to personal behaviour and business capacity on supply chains, asset prices and other factors will drive business investment.

- Positively, with the banking and other high productivity sectors relatively robust, the bounce back might be stronger than expected (stronger than after the 2008 recession), especially if investment in new technologies and skills is triggered.

- Negatively, the key is how much capital, human and physical, has been scarred (rendered obsolete or uncompetitive) by the pandemic.

Several other labour questions need to be resolved: what will happen to participation rates, home working trends and key worker net immigration? Will higher unemployment be short-lived or persistent?

Moreover, how will government finances and monetary conditions be managed? Tax rises will be needed to support public sector net wealth accumulation, rather than simple debt reduction. The government hints that the policy focus should be on household inequality, business resilience, environmental sustainability and regional levelling up, through investment in productivity-building infrastructure and employability. With the UK transition deal likely to cause a drop in productive immigration and FDI, not least for the City, the fear is that long-term UK growth potential suffers.

Also, there is concern that the short-term inflation level will rise, though maybe not permanently. There is already price pressure from restricted electronics supplies and other components. Higher commodity prices and freight costs are expected, perhaps reinforced by some increase in protectionism to underpin local resilience. Near term, underlying inflation rates may remain benign, but a series of ‘steps up’ may warn of future impacts from loose monetary conditions.

If the COVID-19 pandemic is brought under control, there should be a switch back from goods to services in terms of activity growth. Add in the long run effects of recent excess, but necessary, monetary and fiscal expansion and some forecasters are worried about deflation in 2021 being followed by inflation in 2022 and beyond. Much will depend on the relative weight of higher labour costs and productivity growth, together with policy approaches to issues of climate change and other multilateral policies and politics.

Economic forecasting can be a mugs game. At best, any prediction comes with high uncertainty and caveats, especially now after such a large shock. Nevertheless, in order to plan for the future, Dorset needs to be aware of factors likely to influence the coming recovery. Hopefully, this blog has started to prepare relevant ground by indicating broad local sectors and factors that will be important: the skills and innovation that will increase local competitiveness in the long run.